As the world’s appetite for technology and sustainable energy solutions such as mobile phones, electric vehicles, medical devices, and wind turbines grows, we turn to critical minerals to provide the materials we rely on.

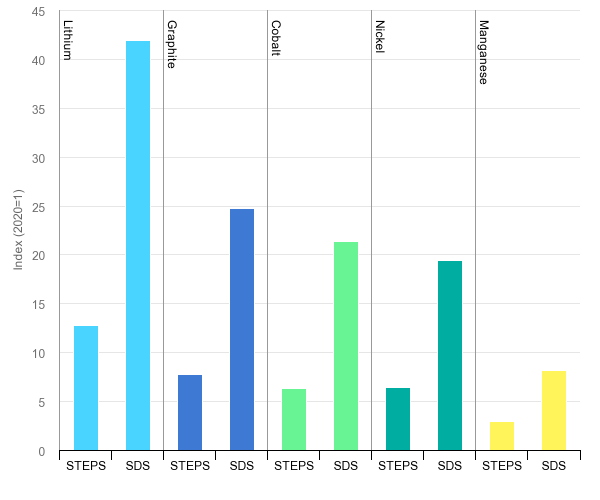

I am sure a good number of those who, like me, earn their living within the Mining, Natural Resources and wider Industrial sector have already been challenged by their children about global warming and questions about environmental consciousness and culpability. Explain to them that the electric vehicle that transports them and the screens they gaze at would not exist without the Mining and Energy sectors’ activities and they quickly move onto the next subject. The fact is, we now live in a world where graphite, lithium, cobalt and many more speciality minerals are propping up our modern existence, and demand for these items is estimated to quadruple by 2040.

Critical minerals are the building blocks for net-zero carbon, however overseas extraction and refining have left the UK and many other countries without a secure supply chain for what it needs production-wise. How, exactly, are the UK government and EU to guarantee supply?

Earlier this month, the Critical Raw Materials Act was announced by the EU’s President von der Leyen aimed at addressing dependency on imported critical raw materials by securing a sustainable supply. It proposed a comprehensive set of actions to ensure a secure, diversified, affordable and sustainable supply of critical raw materials to its member states. The most progressive section turns to the ‘joint purchasing’ of raw material to not only secure supply, but also establish national reserves for the EU in times of crisis. Another highlight of the document involves streamlining the permitting process, an issue which has severely hampered efforts until now.

Last July, the UK government published its strategy for competing against state-backed Chinese companies who currently dominate the supply chain. Industry broadly welcomed the strategy, which has a strong domestic focus on the potential in Cornwall and Devon to extract lithium, tungsten, tin and cobalt, and lithium explorers and refiners active in the North-East of England.

It is encouraging to see pragmatic responses coming into play, especially such pivotal plans as the EU is taking to the magnitude of the problem, and I hope that the UK and EU will share openly on this hot topic. But what does this all mean for talent and the technical and leadership capability that will guarantee this transition?

I will be keen to ask this question when I attend the Mining World Congress 2023 in London on 27th and 28th April where we will hear keynote speeches on ‘How Industry and Governments Can Collaborate Moving Forwards’ and ‘Critical Minerals and Geopolitics’. All the plans in play for localisation of talent and new approaches to international supply chain management are going to require some planning, not just for now, but in readiness for 2040 and beyond. My feel is that despite this drive for greater localisation of supply, there will be a continuing need for a strong representation of overseas talent in engineering, geosciences, commercial and supply chain, to support that change. Let us see how this challenge is perceived - I am looking forward to hearing or instigating this debate.